Within Rocky Fork lies a significant historic site, less than a mile from the parking area, near the confluence of Rocky Fork Creek and Flint Creek, where several old farm fields are now. In January of 1789, during the short-lived State of Franklin movement, John Sevier lead a militia to attack a group of Native Americans camped there for the winter. The camp was destroyed, 145 natives were killed and buried there, and the rest escaped or were taken captive in what was one of many military engagements between Sevier’s militia and natives in what we know as the Chickamauga Wars.

After moving to the area, I heard numerous versions of this story, most of which included an Indian village being wiped out by soldiers with a Gatling gun. The site was neither a village nor wiped out using a Gatling gun, which was not invented until the early 1860s. I have combed through history books and libraries attempting to learn the true story, and with the help of historians Lamar Marshall and Chuck Hamilton, give you here the best version I can.

Prior to the revolutionary war, an agreed-upon line existed basically running along the crest of the mountains, visible to the east from Rocky Fork. Settlers from the colonies to the east were not to cross the mountains into Indian territory. In the aftermath of the war the state of North Carolina was extended west all the way to the Mississippi River. These new lands of the state were wild, sparsely inhabited, and the long-time home of the Cherokee, Creek, and other Native American groups. The loyalty of these native groups was divided since the French, English, and Spanish had been present there, befriended the Indians through trade, and sought their help to check western expansion of the colonies. White settlers from the east now spread across the mountains into land only recently claimed by the new United States of America and the infrastructure of government and military protection did not yet exist.

The newly enlarged state of North Carolina, in an effort to rid itself of debt to the federal government due to the war effort, ceded the new lands back to the government to be used to form a new state, then rescinded the cession, and later ceded the lands again, for good. Amidst the confusion, the State of Franklin movement began, in which Sevier along with a number of others declared their own state and formed their own militia to protect themselves where North Carolina could not or would not. The State of Franklin movement only lasted four years. The state of North Carolina never recognized Franklin as legitimate and the movement dissolved; loyalty remained with North Carolina. The lands to the west first became The Territory South of the Ohio, and a few years later became the new state of Tennessee and Sevier its first governor.

The native groups were divided themselves with many realizing the futility in resisting the overwhelming surge of white settlers and choosing to move on or assimilate, and others wishing to stand and fight for their homelands despite the unlikeliness of success. Those continuing to resist followed leaders like Dragging Canoe, Bloody Fellow, Old Tassell, Kitegisky, Glass, Little Owl and John Watts, and early in the resistance camped on Chickamauga Creek near current day Chattanooga, TN. These resistance warriors became known as Chickamauga for the name of the creek and were not a separate tribe.

John Sevier was a notorious Indian fighter and the military leader of the State of Franklin attempting to make the area safe for settlers. Sevier fought many battles with the Indians and destroyed many Indian towns prior to the Flint Creek engagement. As part of the effort to rid the area of Indians, bounties were paid for Indian scalps, prisoners routinely taken for later exchange, and Indian towns looted for anything of value Sevier and his raiders could carry away.

Following a big victory for the Indians at Lookout Mountain in 1788, a band led by John Watts split off from Dragging Canoe’s band and attacked Gillespie’s Station on the Holston River where they took 28 prisoners. The band then attacked White’s Fort and Houston’s Station and then camped on Flint Creek in the area we now know as Rocky Fork.

During this time Sevier was attacking Indian towns in retaliation and destroyed many. Those Indians not continuing to resist with leaders like Dragging Canoe and John Watts moved out of the area to the west and south. In January of 1789, Watts and his band were camped on Flint Creek and scouts had reported this to Sevier along with a report that the group intended to attack Sevier who quickly organized his militia to march on the camp. Sevier divided his troops to surround the camp and lead a surprise attack, which led to “a complete victory” which he described in a letter reporting the incident to his fellow officials of the State of Franklin. The letter is transcribed below and appeared in several newspapers in Charleston, SC, and Augusta, GA, a short time afterward. This was one of only two official reports made by Sevier of his 35 battles with the Indians:

“It is with the utmost pleasure I inform your honors, that the arms of Franklin gained a complete victory over the combined forces of the Creeks and Cherokees, on the 10th inst. Since my last, I received information that the enemy were collecting in a considerable body near Flint Creek, within 25 miles of my headquarters, with an intention to attack me. To improve this favorable opportunity, I immediately marched my corps towards the spot and arrived, after enduring much hardship by the immense quantities of snow and piercing cold. On the morning of the 10th inst., we were within a mile of the enemy. We soon discovered the situation of their encampment by the smoke of their fires, which we found extended along the foot of the Appalachian Mountain. I called a council of war of all the officers, in which it was agreed to attack the enemy without loss of time; and in order to surround them, I ordered Gen. M’Carter, with the bloody rangers and the tomahawk-men, to take possession of the mountain, the only pass I knew that the Indians could retreat by, while I with the rest of the corps formed a line extending from the right to the left of their wings. The arrival of Gen. M’Carter on the mountain, and the signal for the attack was to be announced by the discharge of a grass-hopper, which was accordingly given and the attack begun. Our artillery soon roused the Indians from their huts; and, finding themselves pretty near surrounded on all sides, they only tried to save themselves by flight, from which they were prevented by our riflemen posted behind the trees. Their case being desperate, they made some resistance, and killed the people who were serving our artillery. Our ammunition being much damaged by the snow on the march, and the enemy’s in good order, I found it necessary to abandon that mode of attack, and trust the event to the sword and the tomahawk; accordingly gave orders to that purpose. Col. Loid, with 100 horsemen, charged the Indians with sword in hand, and the rest of the corps followed with their tomahawks. The battle soon became general, by Gen. M’Carter’s coming down the mountain to our assistance; death presented itself on all sides in shocking scenes, and in less than half an hour, the enemy ceased making resistance, and left us in possession of the bloody field. The loss of the enemy in this battle is very considerable; we have buried 145 of their dead, and by the blood we have traced for miles all over the woods it is supposed the greatest part of them retreated with wounds. Our loss is very inconsiderable, it consists of five dead, and 16 wounded; amongst the latter is the brave Gen. M’Carter, who, while taking off the scalp of an Indian, was tomahawked by another whom he afterward killed with his own hand. I am in hopes this brave and good man will survive. I have marched the army back to my former cantonment, at Buffalo Creek, where I must remain until I receive some supplies for the troops, which I hope will be sent soon. We suffer most for the want of whiskey.”

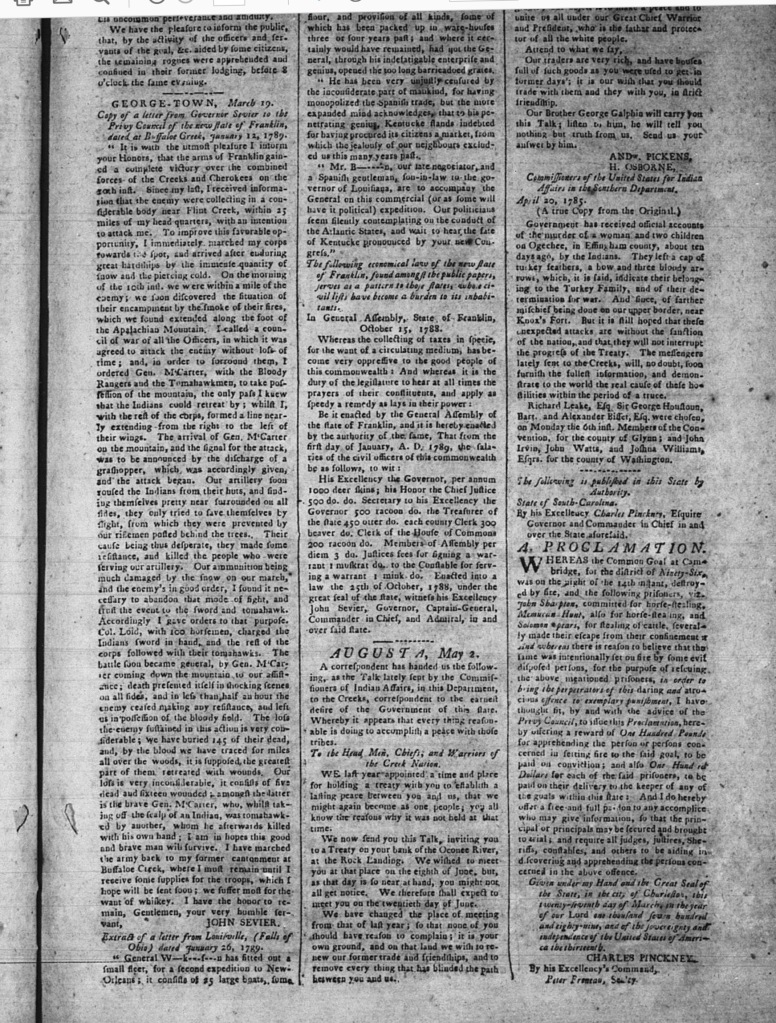

If you had been around in 1789, and in Augusta, GA, in May, you could have picked up the May 2 edition of the Augusta Chronicle, which contained Sevier’s letter announcing his triumph over the Indians. On the same page can be found an article announcing salaries which had been set for officers of the fledgling State of Franklin, with the top officials salary being 1,000 deer skins per year. Unlikely as it seems, the Library of Congress has a microfilm record of that paper and a photo is included here so you can read the news of the Flint Creek massacre just as folks in 1789 did.

John Brown in his 1938 Old Frontiers says “Flint Creek was the bloodiest of all fights in the Cherokee wars.” The State of Franklin movement would end one month later when Sevier pledged allegiance, once again, to North Carolina and thus this event, more a massacre than a battle, became known as “The Last Battle of Franklin.” In April, Sevier sent word to the Indians that he wished to make a deal and a prisoner exchange took place in which at least two prisoners taken at Flint Creek, a chief named Cotetoy and the daughter of Little Turkey, were exchanged for at least two members of the Brown family, Joseph and his sister Polly.

Although not the end of Indian hostilities, this was a devastating blow to the Chickamauga band, which scattered west and south and no longer posed a significant threat to settlers moving into the upper east Tennessee area.

Sources of information about the Flint Creek Massacre include:

The Overmountain Men by Pat Alderman, 1970

Old Frontiers by John P. Brown, 1938

History of the Lost State of Franklin by Samuel Cole Williams, 1889

John,

You have done an amazing job researching this very significant, but little known, historic battle. Thank you! The true story of the Battle of Flint Creek needs to be widely disseminated.

LikeLike

fascinating, incredible work john. many thanks for making this available to all!

LikeLike

Thanks for this post. I was heading out for a little hiking at Rocky Fork last Monday anyway, and after reading this was inspired to revisit the battle site. With snow on the ground, and temps in the 20s, it wasn’t too hard to imagine the conditions at the time of the battle, although I had the luxury of synthetic clothes and a nearby car (and no armed conflict).

LikeLike